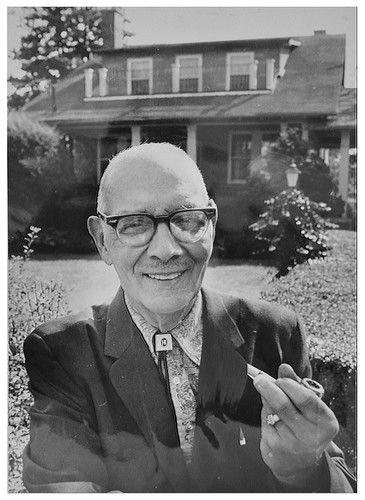

Edwin Bancroft Henderson, a long-time civil rights warrior and advocate of physical education for black children, is shown in an October 19, 1965 photo outside his home in Falls Church, Va.

At the time Henderson was about to move to Alabama to live with his son.

Henderson had a long and colorful career as a civil rights activist–the man who established black basketball, led the building of the black 12th Street YMCA, led integration of the Uline Arena and AAU boxing, among many other achievements. He established an NAACP branch in what was then rural Falls Church and headed the Virginia state NAACP. He was not only a target of white supremacist legislators, but of the Ku Klux Klan.

The following is written by Dave Ungrady and appeared in the Washington Post September 8, 2013:

When E.B. Henderson stopped by the District’s whites-only Central YMCA one night in 1907 to watch a basketball game, he was familiar with the sport. Henderson had studied basketball while attending Harvard’s Dudley Sargent School of Physical Training, which was affiliated with the Springfield, Mass.,YMCA, site of the first basketball game in 1891.

After Henderson and a future brother-in-law, Benjamin Brownley, sat down, the athletic director asked them to leave. White members were concerned that allowing blacks could cause other white members to avoid the club. Henderson felt humiliated.

But that December, he staged the first known blacks-only basketball game in Washington. It was at True Reformers Hall on U Street – a team of high-schoolers beat Howard University 12-5. And then he started raising money for the District’s first YMCA building for blacks.

The Rockefeller Foundation pledged $25,000 to the national YMCA if the black community could raise matching funds. Henderson chaired the committee and brought in the largest amount. He was awarded a $10 gold piece for his efforts.

In 1912, the 12th Street Branch of the Metropolitan YMCA opened in Northwest.

Henderson is being inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on Sept. 8 for his vision to develop basketball for African Americans, who today command a presence in the sport unlike that of any other race.

"He took the approach that sports was extraordinarily important to African Americans," says David Wiggins, a sports historian and a professor at George Mason University. "Sports was one of the ways African Americans could prove themselves, to compete and achieve excellence. It gave them a great deal of satisfaction and respect."

Susan Rayl, associate professor of sports history at the State University of New York College at Cortland, says Henderson, more than anyone else, used basketball as an educational tool for blacks.

"Without E.B. Henderson you would have had a much slower introduction of basketball to African Americans," she says. "He was the catalyst. He was a root, and the tree sprang from the root in D.C. for African Americans. His induction into the Hall of Fame is not just a good thing; it’s absolutely necessary if you want to tell the true history of the game."

Edwin Bancroft Henderson was born in 1883 in his grandmother’s house in Southwest Washington. The family moved to Pittsburgh in 1888 so his father, William, could earn better wages as a day laborer. His mother, Louisa, taught him how to read at an early age, and he monetized the skill, earning a quarter from an elementary school teacher each time he read to her class.

Henderson’s family returned to Washington in 1894. He attended the Bell School, near the Capitol, and enjoyed the access to books in the Library of Congress and to the galleries in the U.S. House and Senate. Henderson credited those books and the time spent watching Congress with teaching him what he called the "perplexing social, economic and political problems of the day."

Henderson was an honor roll student at M Street High School, a pitcher on the baseball team and an offensive lineman on the football team; he also ran track. He was the top-ranked graduate in 1904 from Washington’s Miner Normal School, which prepared students to teach in Washington’s black public schools.

At Harvard he became the first black man certified to teach physical education in public schools in the United States. He borrowed money to pay the $50 tuition and transportation costs, and he worked as a waiter at his boarding house to pay for meals.

In 1904 Henderson also started teaching physical education at Bowen Elementary School in Washington and exercise classes twice a week at M Street High School and Armstrong Tech. At that time, Henderson believed that the more restricted space and a lack of leisure time associated with urban life prevented blacks from engaging in consistent exercise, making them more prone than whites to disease.

"It is unfortunately true that the vitality of the Negro youth is seriously undermined by the crowded city," he wrote in 1910. "Many young men leave our secondary schools and colleges to engage in strenuous work, amidst varying conditions with bodies unsound and but few, if any, hygienic habits formed for life. … it is necessary that we build up a strong and virile youth."

Pushing for better exercise facilities for blacks became a mission for Henderson. He asked the District’s superintendent of black schools to include a gymnasium as part of plans for an addition to Armstrong. He remembered the superintendent’s laughing response. "My boy, they may build gymnasiums in your school in your lifetime, but not mine."

White athletes dominated then, mostly in baseball, but a number of black athletes had gained prominence in football, track and field and especially boxing. Peter Jackson, at 6-1 and 212 pounds, was considered the best heavyweight boxer in the late 1800s and was known as the "Black Prince." Jack Johnson was the first African American to win a heavyweight title, in 1908.

But blacks were behind whites in developing fitness programs. Of the 1,749 YMCAs in the United States in 1904, 32 were for blacks but had significantly fewer resources.

Washington’s thriving black middle class, with its strong school system and vibrant social club scene, framed a prime area to develop an equally dynamic sports environment for the black community. All it needed was someone to spearhead the movement.

Henderson formed the D.C.-based Basket Ball League, which started play in January 1908 with eight teams. It played games through early May on Saturday nights at True Reformers in a room that was also used as a concert hall.

The games were far from elegant. A balcony surrounded three-quarters of the court, which was set up inside a metal cage on a floor that featured four narrow pillars planted near the corners. Teams relied on prolonged periods of passing that could last several minutes. Jump balls took place after each score. And players’ skills were far from refined. Bob Kuska, author of the book "Hot Potato: How Washington and New York Gave Birth to Black Basketball and Changed America’s Game Forever," writes that "defenders spared no pain in halting [a player’s] path to the basket."

The next year Henderson formed and was captain of the 12th Street YMCA team, which won all its games. By then Henderson was considered a top talent. New York Age Magazine called Henderson, the team’s 5-foot, 10-inch center (centers were considered playmakers then), the best center in black basketball.

In 1910 Henderson made an agreement with Spalding Sporting Goods to write the "Inter-Scholastic Athletic Association of the Mid-Atlantic States," a manual about his athletic work with African Americans in the District. It included articles on training tips and sports ethics, as well as results for track and field meets. He consulted black coaches and directors in the South and published records and pictures from Southern schools. The book sold for 10 cents a copy and is considered the first written by an African American that documented black athletics in black schools.

That same year, intercity matches between black basketball clubs grew more common. Henderson played his last organized basketball game with the team at 27, on Christmas Day 1910, in a tournament against the Alpha Club at the Manhattan Casino in New York. The previous day, he had married Mary Ellen Meriwether, who asked her husband to stop playing competitive games out of concern for his safety.

With his playing career over, Henderson concentrated on coaching, promoting fitness and athletics for blacks, and sports administration. He formed the Public Schools Athletic League to establish competition in track and field, soccer, basketball and baseball among black schools in the District. It was the first public school league for blacks in the country. "I believe that Washington will be the greatest competing center for athletics among Negroes," Henderson said in 1914.

To help league coaches learn basketball, Henderson wrote a weekly bulletin offering tips on training, sportsmanship and diet. The league assigned players from Howard University’s basketball team to teach the game to elementary school players and coaches, stressing teamwork and aggressive defense.

Henderson also worked as an official and founded the Eastern Board of Officials, the first organization to train black officials. For more than two decades Henderson worked as an official for football, basketball and track and field and served as the group’s first president. But he struggled to recruit and keep officials, due in part to blacks being paid less than whites. Sometimes black officials worked games for no money or, on occasions, two free game tickets.

In 1912 Henderson had moved to Falls Church, where the challenges facing blacks were even greater than in the District. When he asked a white superintendent to help black children, he was told the concerns of white children had to be met first. "The implication was that the colored children were ours to provide the buses for and buy land for schools, but that only the white children belonged to the county and were to be provided for by tax money," he said.

In 1915, Falls Church’s all-white town council ordered all blacks to live within a restricted area. Henderson was among the blacks who owned property outside the area, and he helped form the Colored Citizens Protection League to fight the order. They filed a suit preventing enforcement, and the Town Council rescinded the order after a court ruled it was unconstitutional.

Henderson formed the first rural branch of the NAACP, there in Falls Church, in 1918. But Henderson’s actions also brought unwanted attention. In the 1920s, he received a letter signed by the Ku Klux Klan that referred to blacks as "baboons" and threatened that he would be "borne to a tree nearby, tied stripped and given thirty lashes. …"

In 1938, Dr. Carter Woodson, who was Harvard-educated and had founded the District-based Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915, asked Henderson to write a book about athletic history for blacks. Henderson’s research for "The Negro in Sports" took him back to the Library of Congress, where he’d first discovered his passion for the written word.

Shirley Povich, a Washington Post sports columnist, addressed in 1950 the book’s social impact: "Henderson resists what might have been the high temptation to gloat at the sensational successes of the Negro boys when finally they got their chance to play in big leagues. Instead, he pays tribute to the American sportsmanship that sufficed, finally, to provide equal opportunity."

After Miguel Uline opened the Uline arena in the District, he banned blacks from attending Ice Capades events, Henderson claimed, because Uline opposed blacks viewing entertainers in revealing attire in a social environment. In the 1940s, Henderson started a picketing campaign, prompting Uline to lift the ban.

At Henderson’s urging, Washington Post president Eugene Meyer helped prompt the District to integrate professional boxing. The local branch of boxing’s governing body at the time, the Amateur Athletic Union, declared that promoters would be denied permits and athletes would be suspended if they allowed mixed boxing. Meyer threatened to withdraw support of boxing tournaments that excluded blacks, and Henderson organized protests and helped file a lawsuit in 1945. The AAU agreed to lift the sanctions in exchange for withdrawing the suit.

"These results made it possible for our boys to measure their abilities against any and all, and did a lot to raise the level of respect of all citizens in our community," Henderson told Leon Coursey, who wrote his dissertation on Henderson.

While fighting against unequal treatment of blacks, Henderson commuted daily to his job teaching physical education in Washington. His afternoons were more idle, though, and he passed the time writing sports articles, including some for the Washington Star about football games he worked as a referee. Henderson had begun his sports writing career before high school, compiling results of games in which he participated. "I walked a couple of miles to the office of the Washington Star to have it published for one penny a line," he told Coursey.

Henderson practiced advocacy journalism in remarkable volumes, claiming to have published 3,000 letters to editors in more than a dozen newspapers. In those letters he tried to discredit discrimination and promote a sense of awareness and dignity for African Americans. In a letter published in The Post on June 26, 1951, Henderson refers to a lawsuit seeking a ban on segregated schools:

"The current suits … are causing turmoil in the minds of politicians, racial bigots, whites and Negroes who profit by or exploit segregation. … In those social areas where sudden elimination of segregation has come about, almost nowhere have any of the fears materialized. For example, Negroes who have for a long time been conditioned to accept second-class citizenship and denied free access to public offerings, do not rush in when the gates open. Some are so thoroughly indoctrinated with inferior status that they will never seek to be where formerly unwanted."

Henderson drew the admiration of Robert F. Kennedy, who invited Henderson and his wife to the Kennedy house in McLean. Henderson told Coursey that Kennedy said he wished "more Negroes would answer the people in opposition to our views." Henderson’s advocacy came at a price early on, though. For safety, the D.C. police commissioner encouraged him to carry a gun, and his phone number went unlisted for 50 years.

A Washington Star clipping from October 1965 shows an op-ed recognizing Henderson’s strong civic spirit as he planned to move to Tennessee, at 82, to live with his son. The story, headlined "Citizen Henderson," said: "E.B. has been a good citizen in the pure sense of the term. This community will miss him."

Despite a lifetime devoted to exercise and a healthful diet, Henderson developed colon cancer and prostate cancer late in life and died in 1977 at 93.

The festivities for the Naismith Hall of Fame induction began in April, at the NCAA Men’s Basketball Final Four in Atlanta. Broadcaster Jim Nantz announced the 2013 inductees. Then he handed to Edwin Henderson II, E.B.’s grandson who lives in the Falls Church home E.B. built, a basketball jersey emblazoned with "Henderson" on the back and "Hall of Fame" on the front. It was Edwin and his wife, Nikki, who had begun the campaign to get E.B. inducted, in 2005. Edwin called Nikki "the point guard who distributed the ball" in the effort to earn E.B. the induction.

"When I learned who he was," Nikki said, "I thought, ‘Gee, he should be in the basketball hall of fame.’ I thought, ‘Gee, we should just write a letter.’ "

Like E.B. Henderson himself, they both understood the power of a letter.

For more information and related images, see flic.kr/s/aHsmJoDRBw

The photographer is unknown. The image is courtesy of the D.C. Public Library Washington Star Collection © Washington Post.